Mississauga Histories

A piece I wrote as a student in 2019 is now used as a teaching resource at the University of Toronto Mississauga

One day this past July, a book showed up on my doorstep. I wasn’t expecting any orders. I picked it up, confused, until I saw my address written in a scrawl of black ink that brought me back to a time when that same handwriting inked the bottom of my weekly writing exercises, handwriting that belonged to only one person: Robert Grant Price, my former professor, who first introduced me to writing history.

The book was titled “What Happened: Mississauga Histories.” Quirky, mysterious, and thought-provoking—historical features written by six former students captured our campus’ early days. My piece “Expropriations in Erindale” is one of the featured stories. I wrote it in 2019 when I was a second-year student, newly accepted into the Professional Writing and Communication Program. At that time, I still believed I’d work in the psychology field, maybe as a psychologist. I was working as a receptionist at a psychotherapy clinic, but I was slowly beginning to realize that I felt most alive in writing classes like these.

Now, the history piece I wrote is used as a teaching resource for new students.

“Readers learn about homicides in Mississauga in 1973; David Blackwood’s tenure as Artist-in-Residence at Erindale College; the origins of the Theatre and Drama program at Erindale College; the story of how private lands were expropriated to build Erindale College; and the life of Peabody, a columnist at a student newspaper. This book includes a bonus story about Alexander Hall, the first Scot to win an Olympic medal in soccer.”

I still remember the day Price told us about his vision to create a book that captured the forgotten history of Erindale College, now the University of Toronto Mississauga. I’m so grateful to see his vision come to pass.

Six houses started it all

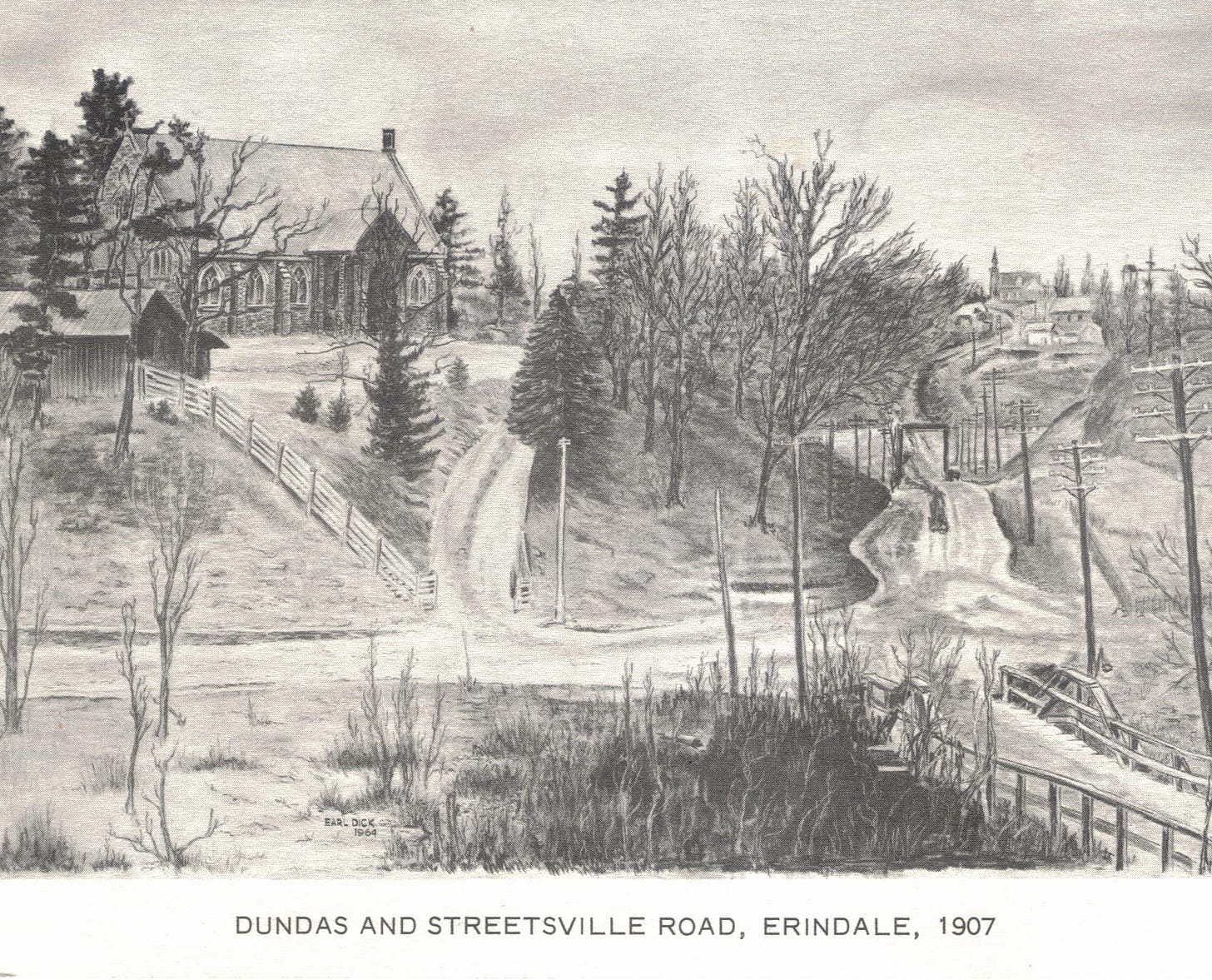

In “Expropriations in Erindale,” I zoomed into the summer of 1965, the epicentre of a long fight between the Ministers of Education and local residents of Erindale who were about to lose their cherished homes to make room for a new University of Toronto campus.

Even though the archives said that the fight against the expropriation turned out in the local residents’ favour, I wondered how the university ended up acquiring the properties after all.

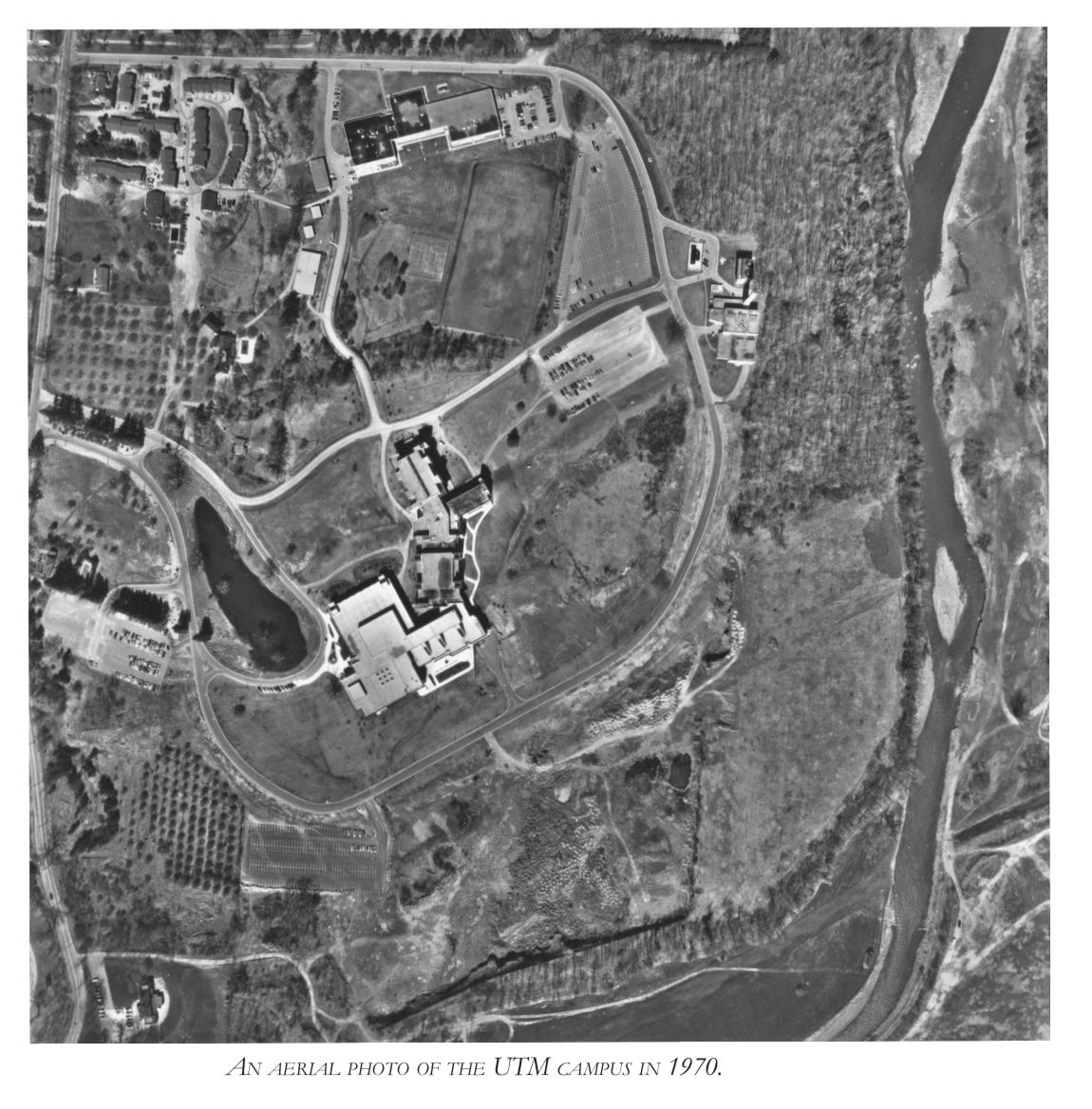

We knew they were acquired because at the new U of T campus, before student residences were built, five all-male houses—Ackworth, Dobratz, McGill, Robinson and Thomas Cottage—and one female property known as the Hastie House served as student residences (and the resting place for wild parties and pranks).

“And then there were the midnight snow-ball fights. If you didn’t lock your door at night, or if you went to bed too soon, when the first snowfall name you would get attacked by a couple of snowballs… There would be evenings where we would drink, eat, sing songs. Sometimes we would get a little loud.” - Arthur Birkenbirgs

Noting that the house names strangely resembled surnames, I began a search to find out if the expropriation actually happened, what campus life looked like in the early 1970s, when the farmhouses disappeared, and where the families were now.

The piece invites readers into conversations with Elizabeth O’Neil, whose father was a key advocate against the expropriation; email exchanges with Dean Emeritus E.A. Peter Robinson who was retired and living in England at the time but whose recounts of “civil mutiny” remained intact; interviews with Arthur Birkenbergs, who arrived as a student in 1972, lived in one of the farmhouses, and worked as parking operations manager at the campus into his later years.

We also take a trip to Heritage Mississauga on Dundas Street West where Matthew Wilkinson and I explore land registry abstracts to find evidence that connects the expropriation story to the six farmhouses that once stood on campus.

Wilkinson confirmed that properties were expropriated, however since they were passed through many hands, it was difficult to track the exact location of the expropriated property. All we knew was that it was in the area where the university stood. Based on the abstracts, two families sold their properties to the university and nine properties were expropriated—despite the university having previously withdrawn their plans to expropriate the cherished lands.

Wilkinson reflected that to name the houses after the families felt a little like rubbing salt in a wound. He grew up in the area and recalled working at the nearby apple orchard where Hugh O’Neil, one of the homeowners and advocates against the expropriation, refused to sell apples to any students or staff associated with the school.

Friends of Erindale was formed to build a better relationship with distrustful local residents, many of whom didn’t know if their homes would be expropriated next, although not everyone agreed that the initiative was successful, despite what the university handbook reports.

There were several un-pretty details uncovered in this story. When I was still a student, I was afraid of what would happen if I wrote the truth. Price reminded me that history shouldn’t be filtered down or changed. At the end of the piece, I strolled through the new residence buildings where no farmhouses remained, still wondering where the families went off to.

Details create the richest account possible

During the writing process, most of my time was spent spent connecting pieces of information I found in the archives. I loved coming to class to hear each of my classmates share what they discovered that week. We built an index of our campus, and like being in an escape room, we worked together to solve clues that would unlock our legacy as students. For the first time in my creative writing program, I was writing something greater than myself. I was so grateful to Wilkinson for offering his time to me. He readily provided all the information he had access to, even though he had a bit of discomfort with another student who published history that wasn’t entirely true.

Writing something untrue was, and is, my biggest fear. Sometimes I uncovered information that made me realize my theories about what happened were all wrong. I could only continue to press in to the discomfort and risk of failure by feeling like capturing this story was my great purpose.

I approached the project with eyes wide-open. The more details I found, the more the story came together. By the end of the semester, I felt satisfied with the answers I found, but I knew there was still a lot missing. My guess is that the former homeowners moved to another town, but most seemed loyal to Mississauga, so I can’t imagine that was an easy move. I made the story dense with years, addresses, and ages of people that have passed, documenting everything I found as accurately as I could. I hoped it would help someone continue the story later on.

When questioning whether people would see the value of this story, as it happened so long ago after all, even longer now that I revisit the story five years after writing it, I see that the value is in the detail.

As Price writes in the introduction, “People die and take stories with them. Whatever evidence is left has to be catalogued and archived and remembered.”

Thank you Robert for including me in this book! I always consider myself lucky to have been one of your students.

Students receive soft copies at no charge and can purchase a copy on Amazon if they wish.